Paediatric Trauma

Pediatric trauma surgery is a highly specialized field focused on treating injuries in children, which can range from minor to life-threatening. This type of surgery involves managing trauma caused by various events such as car accidents, falls, sports injuries, and other types of physical trauma. Due to children's unique physiology and growth patterns, pediatric trauma surgery requires specialized skills, tools, and techniques compared to adult trauma care.

Pediatric trauma surgery include:

- Multidisciplinary Approach: Pediatric trauma surgeons work closely with emergency physicians, anesthesiologists, pediatricians, orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, and radiologists. Often, a trauma team will also involve social workers and rehabilitation specialists to address the full spectrum of the child’s recovery.

- Age-specific Care: Children's bodies are constantly growing, so pediatric trauma surgeons must be aware of the effects trauma can have on development. Injuries to growth plates, head trauma, or damage to internal organs may have long-term consequences for growth and development.

- Minimizing Psychological Impact: Pediatric trauma surgery often takes into consideration the emotional and psychological well-being of the child and their family. Surgeons aim to reduce pain and trauma associated with the surgery and recovery process.

Common Injuries:

- Head Injuries: Concussions and more severe traumatic brain injuries are common in children.

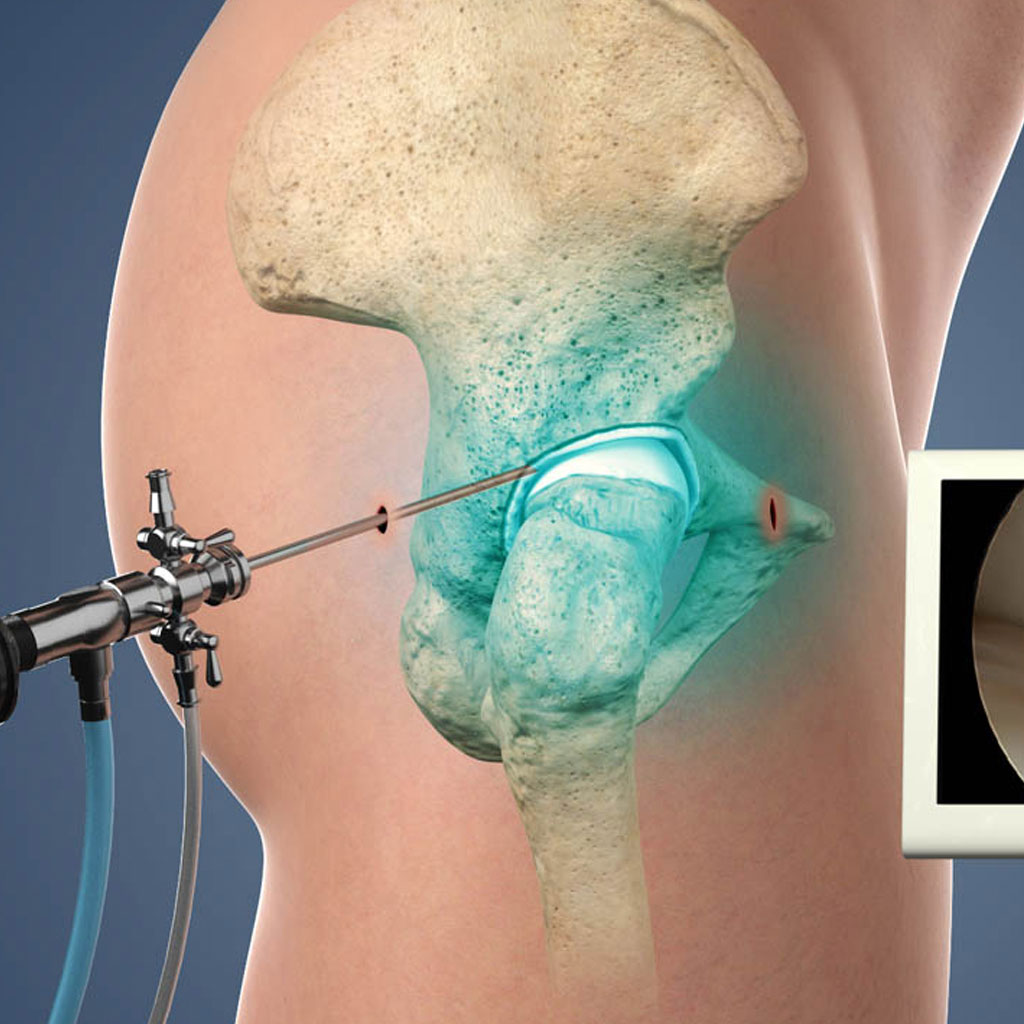

- Orthopedic Injuries: Fractures, particularly of long bones like the femur, are frequent.

- Abdominal Trauma: Injuries to internal organs like the spleen or liver can occur in severe cases.

- Thoracic Trauma: Chest injuries, though less common, can involve the lungs, heart, or ribs.

Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation:

After surgery, rehabilitation often plays a crucial role in helping the child regain full function. Pediatric trauma teams focus on physical therapy, pain management, and emotional support for the child and family.